by Daniel E. Smith

Released in 1975 through BBC2’s Playhouse teleplay anthology, Diane remains a relatively underseen work in Alan Clarke’s filmography. This may in some part be due to the undeniable bleakness of the teleplay’s subject matter, focusing on incest and rape and how one (namely, the titular Diane) learns to deal with them in later life. Although such a focus only adds to the perception of mid-century British social realism as a zenith for miserabilism (think Ken Loach’s Kes (1969), or Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963)), Diane displays an unusual optimism that goes beyond this often-problematic hopelessness. Though clearly a work that shares in certain aesthetic and formal austerities associated with British realism, its meditative and compositional expression place it at a contrast to the aesthetic moralism that has plagued – and continues to plague – expressions of authenticity via the realist mode. It is thus worth exploring not just what Diane offers in terms of its commitments to the real and the authentic, but what these offerings mean in the context of broader British realism: its pessimism, its contentious radicalism, and its expressive austerities that betray a lingering guilt in the post-imperial national conscience.

Whilst apparently well-positioned to act as a vital systemic critique, realism in and of itself does not offer a radical perspective. The problem with claims to realism is how one defines the ‘reality’ upon which the realism is predicated, and British social realism has long struggled to come to terms with the fundamentally contentious nature of the reality it takes as rational and authentic. The 1930s films of the Empire Marketing Board (EMB) that aimed to capture the ‘real’ Britain were often top-down efforts by white upper/middle-class filmmakers that used colonially tinged vocabulary in their justifications for filming Northern and English regional “wilds” and “natives” (Cunningham, 2008, p. 158). Whilst they embraced the mechanics of Soviet montage, with films like Night Mail (dir. Harry Watt and Basil Wright, 1936) heavily influenced by the 1929 Soviet film Turksib (dir. Viktor Turin) and the work of Dziga Vertov, British documentarian John Grierson expressed disdain towards aestheticism and the “fiddle-faddle” of the avant-garde (ibid., p. 161; Miller, 2011, p. 3). By the 1950-60s, the British New Wave (as opposed to the French nouvelle vague) was happier embracing the formal and narrative tenants of cinéma-vérité and Italian neorealism; quite in contrast to the formally and narratively confrontational practices of Cahiers du Cinéma, the Left Bank, and – elsewhere – the post-war American avant-garde and other international ‘new waves’. Despite its claims to a radical confrontation with the realities of post-war British life, it did so at a depoliticised remove that forewent the political alternatives of socialism and pushed against the “effeminacy” and “superficiality” of narrative and formal expression

(Trifonova, 2024, p. 130). Both the Documentary Film Movement and the British New Wave are demonstrative of a difficulty within the British realist legacy to surmount the familiar repression that is British stiff-upper-lipism. Buried in this fear of emotionality and joy is an unspoken guilt, where narrative pessimism and aesthetic austerity allude to an inability to come to terms with the end of empire; the end of material sovereignty over a global supply chain built on a violence and exploitation which could no longer be so invisible to citizens of the metropole. Where the EMB expressed a desire to preserve colonial infrastructure through a strange intermingling of socialism and imperial bureaucracy, the British New Wave represented the stark post-war realisation that without that colonial infrastructure, Britain’s imperialist pseudo-socialism had no legs.

Contemporary realist cinema – what could be read as a kind of British liberal cinema of authenticity – positions itself as beyond the colonial. Representation of communities that were once the subject of imperial rule (e.g. West Indian and Asian migrants, regionalism), or of mass moral and legal panic (e.g. narratives of queerness, alternative domesticities), are now stronger than ever despite an equally-strong reactionary backlash. Yet unaccounted for here is a creative and formal undercurrent that views certain technical and aesthetic formula as pragmatic. British cinematic realism has instead traded pessimism for an increasingly fraught neoliberalism optimism. Films like The Full Monty (dir. Peter Cattaneo, 1997) and Brassed Off (dir. Mark Herman, 1996) form a semi-realism rooted in the authenticities of the British New Wave, but avoid immiseration by focusing on what Mark Fisher identifies as a new optimistic masculinity born of rational “entrepreneurialism” (Fisher, 2020). These narratives of identity and marginalisation are authenticated through the industrial and ideological logics of capital, circumventing the deep relationship between colonialism and capitalism. Industrially, chains of independent British producers now treat the Hollywood industrial and aesthetic model as pragmatic, implying that to diverge from the model is to dilute authenticity. The result is a slew of 21st century works – such as The Last Bus (dir. Gillies MacKinnon, 2021), Fisherman’s Friends (dir. Chris Foggin, 2019), and Allelujah (dir. Richard Eyre, 2022) – that are anxious to appear moral, but in this post-imperial guilt, turn to neoliberal logics even as neoliberalism continues to power colonial action. A similar critique can be levelled at the post-2008 works of Ken Loach, whose politically urgent films risk taking on a pessimism that is not automatically nihilistic but is, as Martin Hall notes, overly concerned with subjects who lack any systemic agency or collectivist spirit (Hall, 2020, pp. 138-139). The term ‘post-colonial melancholia’, as coined by cultural theorist Paul Gilroy, is usually reserved for the more explicit manifestations of imperialist nostalgia or contemporary reactionary politics; a self-satisfying guilt that evades systemic critiques of colonialism in favour of an inadequate and deflective superficiality. Yet this too easily isolates conservatism from the fact that this melancholy born of post-colonial economic decline is more universal to British life than some would care to admit. That British film chooses to eschew political and emotional alternatives in favour of a socioeconomic system which perpetuates colonialist logics under the uncanny guise of acceptance and austerity is the reason that the industry – and its odd relationship to the continental and international avant-garde – has always felt in limbo.

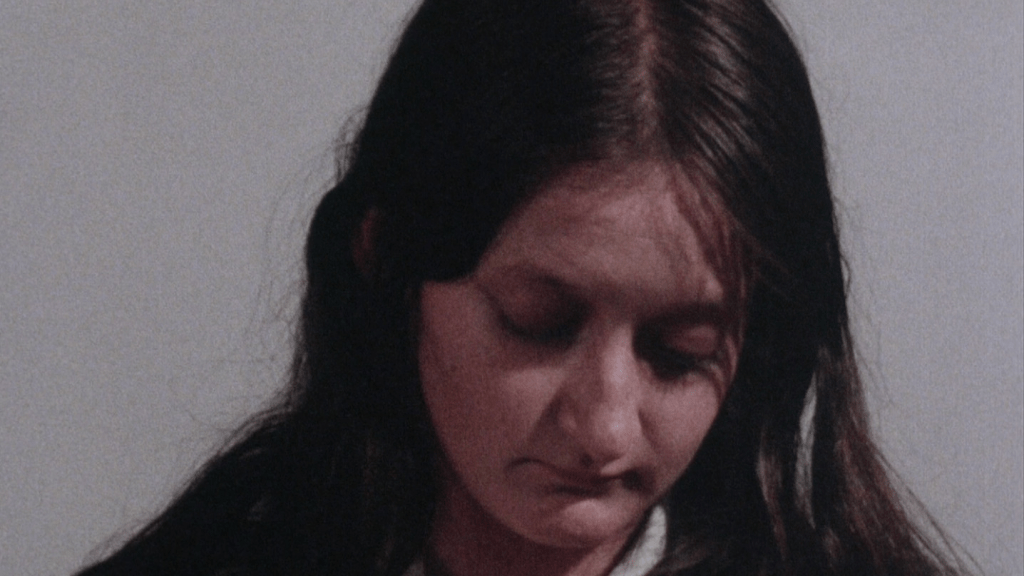

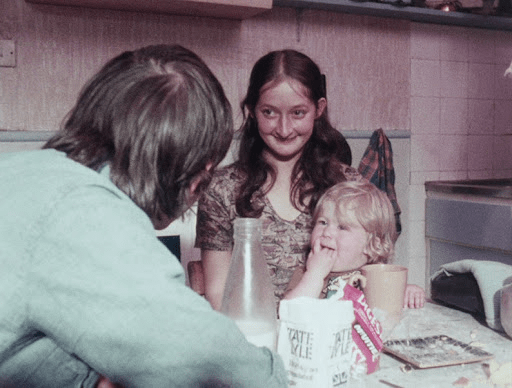

In returning to Diane, I want to caution: Diane is not the curative text for overcoming post-colonial melancholia. Like its British New Wave precursors and teleplay contemporaries, it too can often lapse into a futility that is both within and beyond it. What makes Diane stand out is that, in its attention towards the real, its bleakness is not a nihilistic marker of authenticity but one part of a broader emotional trajectory. The first half of the teleplay depicts a thirteen-year-old Diane – a debut performance by Janine Duvitski (credited as Janine Drzewicki) – as distant and irate; struggling to navigate her romantic life with the unresolved tensions of sexual abuse hanging over her. Yet by the second half, an older Diane – clearly more at peace, but cautious in her calmness, after spending some time in care – has begun to navigate a new social and romantic life. It is not so stridently optimistic as to suggest some utopian endpoint for Diane. She still struggles with intimacy, and is burdened by a feeling of responsibility towards her father which she only begins to process on his deathbed. What is important is how the narrative does not position these issues as a pure conclusive nadir. In the second half, Diane encounters two new romantic interests. The first, Harry, is a regular visitor at the petrol station she now works at. Whilst he pressures her into a date, she cannot help but deny some attraction towards hum and agrees to start seeing him. The second, Kevin, is a neighbour with whom she shares a small flat complex. Though neither of them express any explicit affection towards each other, the comfort that Diane feels around him comes in part from a more invitational approach into his personal life. In the end, Diane has to admit to Harry that whilst she is smitten, she cannot offer him the kind of romance he wants. With Kevin, romance feels possible but both are content to let it linger in this in-between space between the romantic and the platonic. The masculinity she is attracted to appears not to be incompatible with patience; it is confident and inclusive but bereft of the unyielding short-sightedness typical of a masculine hegemonic worldview. These two romances are framed alongside an ill-fated relationship: Diane’s other neighbour Carol and her controlling and aggressive husband Rooney. In presenting Diane as a spectator to his cruelty, Diane’s own trajectory in the second-half switches to one where she is now able to be reflective and see the dynamics of abuse both at a relative distance and through an agency born of empathy.

Highlighting the importance of agency is one way through which Diane is able to surmount pessimism. Rather than play Diane as the passive subject of social structures which enact cruelty onto her, Clarke’s realism portends that individuals both shape and are shaped. Far from being a singularly subjective event, the focus on Diane’s interactions with others displays a radical assessment of trauma and the search for agency as a ripple upon the delicate surface of the social. Decaying collective power – arising from class abstraction, lack of educational access, sexual abuse, and social isolation – has prevented Diane from realising her own agency; from having the time and space to notice and reflect upon the contradictions and violence around her. Indeed, the world around Diane – a Britain caught between the early declines of social democracy and the very early insinuations of a shift towards Thatcherite neoliberalism – is rife with unspoken and unknown tensions which litter and refract the landscape. The boyish sexism and youth disillusionment of some of the boys on the estate rise from this failing structure; forgivable only on the grounds of their youthful naivety but frightening as a prospect for the future. Jimmy, a local choir boy who falls for her in the first half, is far more conscious of his agency – but even then, this is realised through structures of community that are more present for men than for women. When the future arrives for Diane, it is in the revelation of her agency that she is able to form more positive connections. Much of the teleplay’s joy is found in watching Diane both gain the confidence to engage in social life and situate herself in the socio-sexual dynamics of contemporary society.

Diane discovers her agency after intervention from institutional forces, who arrest her father off-screen and presumably bring her into care. Despite readings which suggest that Diane promotes a positive assessment of institutionalisation (Barron, 1975), the actual institutional structures through which Diane is placed are unknown. Indeed, the only structure we know for certain that Diane navigates through is the church, as it is the local reverend Terry who talks to her and gets her to open up about the abuses of her father. There is a similar risk here in assuming that Diane is sympathetic to organised religion as a form of moral-legal salvation; a sentiment with its own relationship to imperialism. However, Clarke’s previous work teleplay Penda’s Fen (1974) – written by David Rudkin – suggests that Clarke’s own view of religion and spirituality is more nuanced than a simple reduction to structural abuse. The protagonist of Penda’s Fen, Stephen, attempts to find a stable identity through traditional Anglicanism: a heteronormative mythos of nationalism, masculinity, and authority.

Yet in the end, Stephen finds more comfort in the religious politics of his father, a local reverend whose own spiritually-broad and open-minded interpretation of Christianity has made him something of a pariah. Clarke’s vision, it would seem, is not to castigate religion from a toxic atheist standpoint but to foreground a lost spirituality; a relationship to the unknown and the sublime that embraces rather than limits. In a way, Terry is his own unusual victim: a man who serves a role of compassion in the community, but who works within a network of structures that make compassion so difficult. He is far more apolitical in tone that Stephen’s father in Penda’s Fen, but this only makes the silent worries and patience on his face all the more pertinent; especially given that Diane’s father is the church groundskeeper. Diane then is not an endorsement of institutionalisation or penal justice. On the contrary, Terry’s placement in the story foregrounds the contradictions of a need for collective intervention even when the failures of this same collective enterprise – of a post-imperial structure unable to comprehend a strong emotional or moral life outside of itself – are responsible for the need to intervene.

In terms of style, Diane’s aesthetic/formal cues are classically realist: long takes, authenticity of performance and dialogue, on-location shooting style, and subject matter. If playwright David Rudkin is to be believed, Alan Clarke himself would have eschewed any claims to artistry and comparisons to European auteurs like Robert Bresson as “bollocks” (Rollinson, 2005, p. 67). Yet Bresson, despite overt political and spiritual differences to Clarke, serves as an appropriate comparison in terms of the perceived tensions between realist and expressive modes. Bresson’s oeuvre has regularly employed these techniques – from Pickpocket (1959) to L’Argent (1983) – and yet his realism is not what can be easily described as realistic. Instead, Bresson’s style gets closer to what Thomas Tam calls an “enhanced realism”; a negotiation of mimesis (put simply, how one represents reality) that foregrounds the process of creation via form and formal manipulation (Tam, 2004, p. 3; p. 6). Regardless of whether Clarke was conscious of this mimetic philosophy, Diane goes beyond the pretences of certain avowed ‘realist’ techniques that imply authenticity and objectivity. The fundamental flaw of seeing poetics through the lens of indulgent subjective expression is the inability to understand poetics as fundamentally social. What is ‘the poetic’ but an understanding that certain techniques and actions can conjure a myriad of intersecting feelings and thoughts in a way that get beyond the mundane? And what does it say of those practitioners and industries who view the arts not as a desire to transcend futility, but to encourage it; to mistake the mundane for an authenticity of feeling? Often those most indulgent poets are those who employ techniques for what they signify rather than the emotional and intellectual potential of these techniques. The 21st-century cult of the long take is a classic example, where a bastardised Bazinian vision of the long take (think 1917 (dir. Sam Mendes, 2019) or the works of Philip Barintini) thinks of itself as unpretentious grounded-ness rather than cultural peacocking.

Diane’s often slow and the languorous takes exceed the requirements of austere and pseudo-objective representationalism, leaning into this slowness to help unify varying intensities within the mise-en-scène. Early in the teleplay, a scene of Diane and Jimmy sitting on the grass in a park goes on without a cut for around six minutes. Whilst the shot brings the subtleties of their interaction into extreme focus, one is also made aware of their locale. The scenery in the park isn’t vibrant or exciting. Instead, it is very flat and constructed, with very few trees and industrial buildings on the horizon. For Diane, and for us, the park is the illusion of escape. The lingering shot is uncomfortably intimate, as Diane is forced to confront her issues with romance via this inadequate illusion. This would imply that Clarke’s use of long shots is more in its capacity to alienate or entrap, but there is a moment in the second-half which contradicts this reading. A largely static shot of Diane helping her neighbour Kevin peel paint off a door with a blowtorch lasts for four minutes. Despite similarities to the scene in the park – of Diane and her potential lover captured in the same shot at roughly ground height – the action within the scene tell a vastly different story. Diane and Kevin move varyingly between the foreground and background; they sometimes face each other and sometimes don’t; their conversations flit between lively and relaxed, but never awkward or forced; they respond to each other as much as they naturally look for a response. The act of repainting the room feels inclusive, organic, and conducive to a sense of agency. It stands at a contrast to the static homogeneity of the shot in the park, stuck in a space and romantic context that feels forced and beyond one’s control. Likewise, the depiction of the room mid-completion implies the possibility of completion; a future which at present is not quite there but is nonetheless tangible. That the shot finishes with Diane and Kevin sitting together in the background, the peeling paintwork and wallpaper all around them, brings them together and into the futurity. The stagnant claustrophobia implied in the first-half is replaced with a new conception of time; one that feels liberated and filled with potential and patience.

Whilst it may seem incongruent and simplistic to state that Diane is a beautiful work, its darkest moments do not desire to linger on the darkness with voyeuristic or exploitational purpose. Its beauty lies in its compassion; a trait best exemplified through its employment of ellipsis, with certain actions left to implication. When Diane walks around her dishevelled flat with her vacant father permanently stuck to the dining table, there is a spectre of unnamed neglect which only comes to the surface later during Diane’s confession to Terry. When Diane finally gives birth to her baby, attention is drawn to the aftermath as a momentary excursion from an otherwise inconsequential moment of two boys fixing a bike. In that moment, Diane places the baby in the estate waste bins, the newborn hidden from our view inside a brown paper bag. In using elliptical techniques, it’s not that the teleplay wants to avoid addressing these problems; instead, its compassion lies elsewhere. Scenes in the flat create a cramped but layered environment where neglect and insularity has seeped into every domestic nook: a haphazard utilitarianism, unwashed dishes, clutter, and a barely-used coat rack. Likewise, placing the moment that Diane throws her baby in the bin in the middle of a minor narrative foray foregrounds Diane’s own lack of agency within the social environment. Here, the estate looms over her in more ways than one: a brief high-angled shot of her approaching the bins, followed by a shot of the two boys, with Diane framed in the background alongside the brown stony exterior of the estate. In these moments, we may not be privy to the full objective truth, but there is an emotional lucidity to these moments which foregoes the idolatry of post-emotional objectivity.

To bring some fairness for what risks being an unfair diatribe against the legacy of realism in British film and television, these works are not bereft of artistry. There may be certain vocal resistances within the movement and techniques employed in the works that imply a problematic claim to authenticity, but let it not be forgotten that many of these works are the results of exhaustive multifaceted labour. Often, how one claims to tap into the real and authentic is more interesting than the notion of reality that is proclaimed. Whilst we can critique the contemporary films of Ken Loach for being too defeatist, they do not entirely lack aesthetic appeal; and certainly neither do they lack a politicised compassion. Loach depicts the Jobcentre in I, Daniel Blake as a blank sterile bureaucracy where despite its claims to humanity, everything and everyone within it seems to act and dress like humanity just gets in the way. And whilst Ricky’s boss in Sorry We Missed You is clearly a character of disgust, there is an undeniable comedy to his post-class gillet masculinity and drab LinkedIn-style proselytising. Going back in time, Diane itself is born of the same institutions and industrial contexts as its realist contemporaries: mid-century teleplays, crumbling social democracy, and Reithian principles (Hendy, n.d.). Pessimistic and problematic as they may have been, these works do nonetheless represent something close to a collectivist and collaborative creative spirit that is now so diffuse and atomised. In that sense, Diane offers something in the present – industrially, aesthetically, emotionally – that British film and television is severely lacking. And for a movement that has long been unable to overcome its guilt and repressions, it stands as a modest exception. One could say provocatively that Diane is an inversion of traditional romance; an affective dimension largely alien from social realism. Perhaps that says even more about the denial of emotional reality that lies at the heart of post-imperial masculinist British realism. Appropriate then, to maybe contradict the thesis of this essay somewhat, that Diane’s view of love is less explicitly romantic. Yet in its bleak realism, it is not unemotional. Love and romance is not impossible, but instead it takes on a new shape; demands things of those who feel it beyond what is traditionally prescribed. With this, love’s roots are written into the systemic politics of the everyday. The fragile foundations of post-imperial social democracy are thus encouraged to move away from guilt and nihilism and towards something more emotionally mature, where new structural realities born of community and compassion may not exist now but still remain possible.

Bibliography

Barron, Charles. (1975). Fine acting not enough for incest play that changed its style. Stage and Television Today, 17 July, p. 13.

Cunningham, John. (2008). The Avant-garde, the GPO Film Unit, and British Documentary in the 1930s. Eger Journal of English Studies, no. 8, pp. 153-167.

Fisher, Mark. (2020). Postcapitalist Desire: The Final Lectures. Repeater Books: London.

Hall, Martin. (2020). The future is past, the present cannot be fixed: Ken Loach and the crisis. In: Austin, Thomas and Koutsourakis, Angelos (eds.). Cinema of Crisis: Film and Contemporary Europe. Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, pp. 136-149.

Hendy, David. (n.d.). The death of Reithianism?. BBC [online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/historyofthebbc/100-voices/radio-reinvented/the-death-of-reithianism/ [accessed 20th January 2026].

Miller, Henry K. (2011). The Soviet Influence: From Turksib to Night Mail [booklet]. The Soviet Influence: From Turksib to Night Mail [Blu-Ray]. British Film Institute.

Rollinson, Dave. (2005). Alan Clarke. Manchester University Press: Manchester.

Tam, Thomas. (2004). Bresson and Mimesis. Kinema, Spring 2004.

https://doi.org/10.15353/kinema.vi.1070

Trifonova, Temenuga. (2024). The working class in contemporary British cinema. Journal of Class & Culture, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 129-148.

Daniel E. Smith (Website: https://danedsmi.com/, @danedsmi95 on X) is an early career researcher and freelance film/culture writer based in the North East of England. His writings focus on the interrelations between media and capitalism; emotionality; form and technology; and radical film theory/practice. He holds a PhD from the University of Leicester, where he researched nostalgia in post-2008 British film and television, and has written previously for academic publication in Film-Philosophy and New Review of Film and Television Studies.

Leave a comment