by Ceridwen Millington

Affliction (1997), starring Nick Nolte, James Coburn, Sissy Spacek and Willem Dafoe is a film that is easy to watch subjectively, feeling pity and anger as Wade Whitehouse suffers the sins of the father. The story follows the aforementioned character, a man is ostensibly a sardonic, alcoholic cop and general town dogsbody. However, in the darker hours he’s tormented by the suffering imposed on him as a child: beaten by his father as he stood up for his younger siblings. The narrative seems to see Wade’s past consuming him, and the man lashing out against the world in tragic inevitability. It’s a mistake, however, to view this tale as another take on Taxi Driver – a work written by this movie’s director and screenwriter, Paul Schrader – as it’s not just about alienation. The frame here is not just focused on the tragic figure at its apparent centre, but brings in the passive, ignorant, and voyeuristic societies that exist on-screen and off.

It’s very much deliberate that the story is framed by the narration of younger brother Rolfe. He posits, at the opening and close (as well as rare other points), the character flaws, pathos, and horrible destiny that is afforded to abused men like Wade. It’s suggested that the arc of well-meaning failure to an angry, abusive, and dangerous individual is a curse passed down across the generations. This careful framing and frequent detachment allows viewers to be absorbed by the story, to feel its emotions and observe the Shakespearean quality of all that unfolds. When the story ends it is easy to forget that Rolfe is not just a passive observer. He is someone who abandoned his abused sibling to his fate; someone who avoided the curse by substituting another in his place. And he is an academic, a historian specifically – and so the tale he tells is not an objective one.

A casual watch, unsurprisingly, gives the sense of something horrible but unpredictable. Rolfe introduces the tale as taking place over a single deer hunting season, and its character as a man eagerly driving his daughter through town on Halloween. The daughter’s line of “I think you used to be bad” does, of course, ring alarm bells about her father’s nature. But he’s a man who seems to have at least a couple of people who like him, not least his girlfriend. And, as the town’s (only) cop, he seems to hold a somewhat-relevant position in society. It seems, then, like a classic a downward spiral: a man largely holding it together who, as things progress, finds himself consumed by his base impulses. His loss of everything by the film’s end makes his starting position seem comparatively enviable.

But believing this to be a simple tragedy, a study of character flaws and fate, is a delusion that comes from buying into the curated tale that we are presented with. The behaviours of Wade are quite erratic from the start: freezing up in thought as if in an absence seizure, huffily disappearing from his daughter to be a boozy passenger instead, and harassing someone for a parking fine despite their father-in-law’s death. This all, of course, is subsumed by the appearance of Glenn Whitehouse on to the scene; the elderly father who has lost nothing of his capacity to dominate a scene. The social context of the story is buried beneath part-Shakespearean, part-Freudian, part-Biblical tale of father against son.

The guilt of those who allow these stories to unfold is addressed a little, as if a little absolution to resolve lingering questions of others’ responsibility. A particularly dramatic scene has family drama recur before the funeral of Wade and Rolfe’s mother. Glenn rips into all his children as the core of a mean, caustic, booze-driven tirade. It is, naturally, Wade who receives the brunt of this once again, his younger brother speaking just a few quiet words. Rolfe’s role as the perpetual observer is hinted before the drama, as Wade’s boss, Gordon LaRiviere, subtly digs at him by stating how he’d have little reason to return to a small town. And his status as an outsider, a voyeur of the little people, is made almost explicit when the camera trains on him whilst Glenn mutters, unseen, “Still standing up for your little brother?” This plays, superficially, like an instance of survivor’s guilt, given the fact that Rolfe disappears from the central narrative minutes later.

But one of the story’s most important threads is the wider abandonment to which Wade is subjected, and which is evident in how his descent into delusion is disregarded. This descent begins almost unprompted, outside of the weight of his normal suffering. Wade, in the weight of trauma and, likely, of powerlessness, begins to suspect that one of his closest friends, Jack, was paid off to kill a powerful man. His girlfriend, however, simply laughs at his suggestion, without questioning the level of delusion that it takes to blame a friend for murder. Rolfe encourages Wade to follow that theory, not considering the consequences. And LaRiviere doesn’t seem to acknowledge his increasingly erratic behaviour or, if he does, reflects it in trying to buy Wade’s happiness through an apparently-overdue car upgrade. Perhaps it’s ignorance or instead a wilful attempt to keep peace, but it allows Wade to slip further into delusions and destruction.

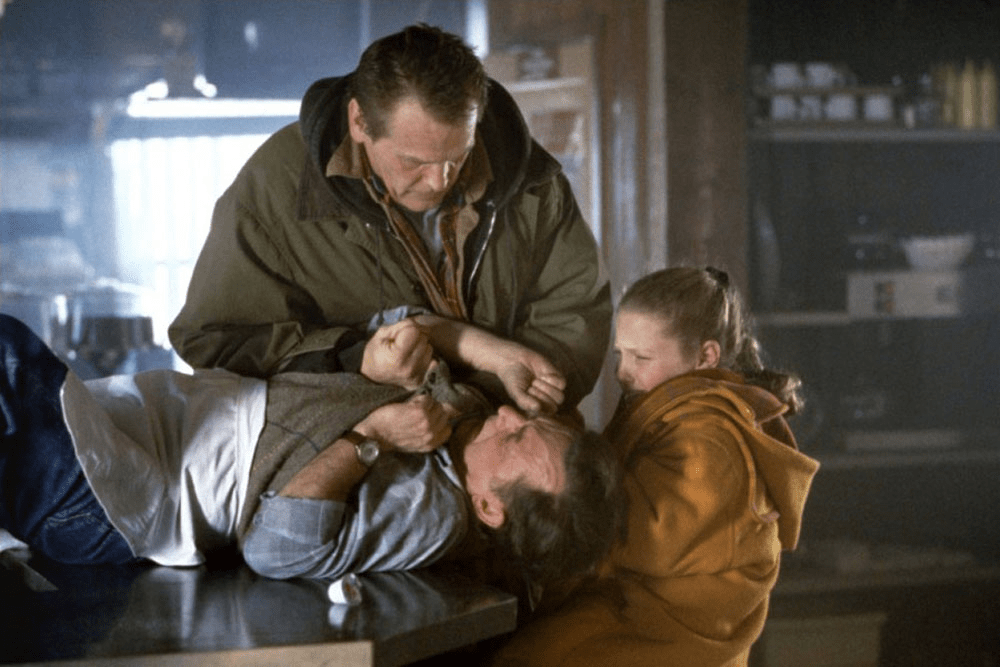

Everyone totally abandons Wade eventually through clearly cutting him off. Wade behaves terribly, of course, in the lead up; whether it’s pursuing Jack into the wilderness, smashing up his boss’s office, threatening his girlfriend’s boss, or launching a custody suit for his daughter. Being fired and being dumped are appropriate actions in this context. A first time viewing makes this feel as surprising as it probably does for the delusional Wade; circumstances going far beyond their control. But a closer viewing reveals this to only be the natural result of the choices made by a community, to neglect a man’s trauma to the point that it becomes unmanageable to all. This negligence leaves Wade and the community in a position of irreversible harm: Wade kills Glenn and Jack before disappearing for good.

The community does deserve some leeway, of course, given the likelihood that so many of its residents are bound up in suffering. This small, working class town seems infinitesimally small and immensely miserable. The opening credits overlay a funereal procession of images showing the town’s limited number of public spaces: a pub, town hall, a cafe. With the people’s willingness to ignore emotional lives, and the weak semblance of cultural life, Wade Whitehouse’s collapse is bound up in the energies of the town. Its own collapse mirrors Wade’s too, with the final, decisive narration revealing it to be have become usurped and nameless in the wake of LaRiviere’s new leisure resort. These layers of suffering suggests that the failures of this community aren’t the source of the film’s drama, but there’s something greater and off-screen that is the real and unnamed power.

Affliction offers layers upon layers of meaning that shift depending on the angle which it’s viewed from. It’s a presentation of a real world scenario: how individual communities allow suffering to continue in their midst. At a more foundational layer, it’s a story of the wider society, only implied by the claustrophobic nature of Affliction‘s world, that allows such desolate communities to struggle and be destroyed. Rolfe’s words, that close the film, of “I continue” can be viewed as a mere call to action: that we should not merely continue but help these people. But, knowing the characters’ role as a passive and powerful spectator of this suffering, it can instead be read as an unconscious, but scathing, judgment. We choose to allow others to be sacrificial lambs to capitalism and its counterpart, abuse, and each tragedy we witness is of collective making.

Ceridwen Millington is a freelance critic and poet based in Bristol, England. Her work of all kinds is frequently about horror, science fiction, and tragedy. A consistent throughline, regardless of genre or form, is an interest in finding sympathetic views towards the maligned; reevaluating ostracised characters and underexplored works.

Leave a comment