by Mary Muñoz

Released in 1935, The Bride of Frankenstein, directed by James Whale, is widely regarded as one of the greatest sequels in cinematic history. Building on the foundation of Frankenstein (1931), the film expands the narrative and emotional depth of Mary Shelley’s original story, while introducing new characters and themes that resonate with modern audiences. Its legacy is not merely rooted in its gothic visuals or Boris Karloff’s haunting performance, but in its layered exploration of identity, alienation and the consequences of creation.

At the heart of the film are two figures: the Monster, whose journey of self-awareness and rejection forms the emotional core, and the Bride, whose brief but potent appearance encapsulates themes of gender, autonomy and spectacle. Together, they embody the film’s meditation on “otherness”: the condition of being cast out, misunderstood and feared.

The Monster in The Bride of Frankenstein is a paradoxical figure; both terrifying and sympathetic. Karloff’s portrayal emphasises the Monster’s vulnerability, especially in scenes where he seeks companionship and understanding, or in those where he is injured by the baying crowd. His alienation is not innate but imposed by a society that sees only his grotesque exterior. The Monster’s violent outbursts are reactions to cruelty, not expressions of inherent evil. This duality of victim and villain forces viewers to confront their own biases about appearance and morality.

A pivotal development in the sequel is the Monster’s acquisition of speech. His famous line, “Alone… bad. Friend… good!” distills his yearning for connection and his growing self-awareness. Language becomes both a tool of empowerment and a marker of his isolation. As he learns to articulate his thoughts, he becomes more human, yet this humanity only deepens his suffering. The more he understands, the more he feels the sting of rejection.

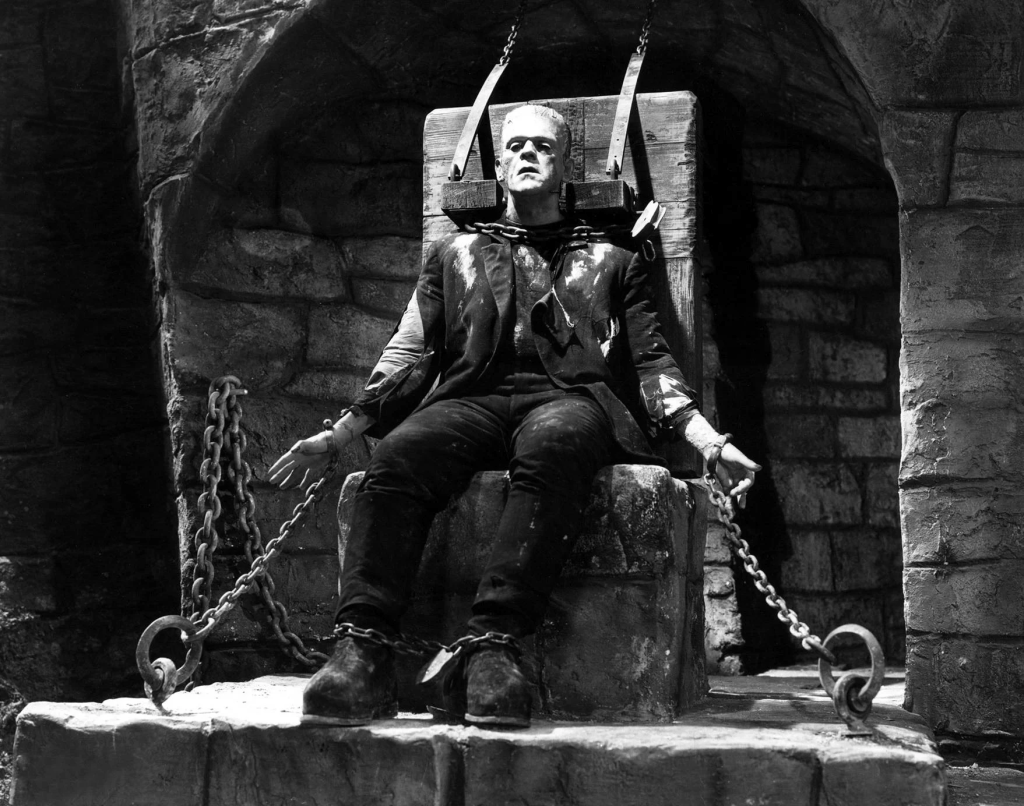

The villagers’ response to the Monster is one of fear and violence. Their mob mentality reflects a broader metaphor: society’s intolerance toward those who are different. The Monster’s attempts at kindness are met with brutality, reinforcing the idea that “otherness” is punished, not embraced. The Monster is burned, hog-tied, poisoned and imprisoned throughout the course of the film. Whale’s depiction of the villagers is unflinching: they are not heroes but agents of exclusion, mirroring real-world dynamics of prejudice and xenophobia.

The Monster’s arc is steeped in religious and mythological symbolism. He is a modern Prometheus, punished for the hubris of his creator. He is also a fallen angel, cast out from paradise and condemned to wander. These layers elevate the Monster from a mere creature to a philosophical figure, a representation of humanity’s struggle with identity, purpose and belonging. His final act of self-destruction is both tragic and redemptive, a sacrifice that underscores his moral complexity.

The Bride, played by Elsa Lanchester, is created not out of necessity but ambition. Dr. Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger) construct her as a companion for the Monster, without her consent or agency. Her creation is a spectacle: lightning, machinery and theatrical unveiling. Yet beneath the grandeur lies a disturbing truth: she is an object, fashioned by men to fulfill a role. Her silence is not just literal but symbolic, representing the erasure of female autonomy in patriarchal narratives. The Bride’s iconic scream and rejection of the Monster is a moment of profound ambiguity. Is it an act of agency, a refusal to be paired with someone she did not choose? Or is it a reflection of internalised fear, mirroring the villagers’ revulsion? Either way, her reaction shatters the Monster’s hope for companionship and seals both their fates. Her brief moment of resistance becomes a powerful statement on the limits of empathy and the consequences of forced creation.

The Bride’s role is emblematic of gender dynamics in early cinema. She is beautiful, silent and doomed: a figure of male fantasy and control. Her lack of dialogue and immediate rejection underscore the limited space afforded to women in narratives of power and creation. Yet her enduring image – a towering hairstyle, wide eyes and bandaged body – suggests a deeper resonance. She is not just a victim but a symbol of resistance, however fleeting.

Despite appearing for less than five minutes, the Bride has become an icon. Her visual design is instantly recognisable, and her story continues to inspire reinterpretations in literature, film and art. Why does she endure? Perhaps because she represents the intersection of beauty and horror; autonomy and objectification. Her silence invites projection, allowing each generation to find new meaning in her brief existence. She is a mirror, reflecting our fears, desires and questions about identity and agency.

The Bride of Frankenstein remains a masterwork of both horror and human inquiry. Together, the Monster and his Bride embody different facets of “otherness”. One is vocal and yearning; the other silent and symbolic. Ninety years on, the film’s themes are more relevant than ever. In a world grappling with questions of inclusion, empathy and identity, The Bride of Frankenstein offers a timeless reflection on what it means to be human – and what it means to be rejected for it. Its gothic artistry may dazzle, but its emotional and philosophical depth is what elevates it beyond a simple “monster movie” to ensure its place in the pantheon of cinema.

Mary Muñoz is a writer and podcaster based in Glasgow. She has had work published in Film Stories magazine and used to be part of the JumpCut Online team as a Feature Writer. She is currently an editor and podcaster for Moviescramble, a content creator for Nordic Watchlist and a regular contributor to the following podcasts: Well Good Movies, Vampire Videos and The Modern Horror podcast. You can find her on most social channels @missmaimepeas.

Leave a comment