by Samuel Leary

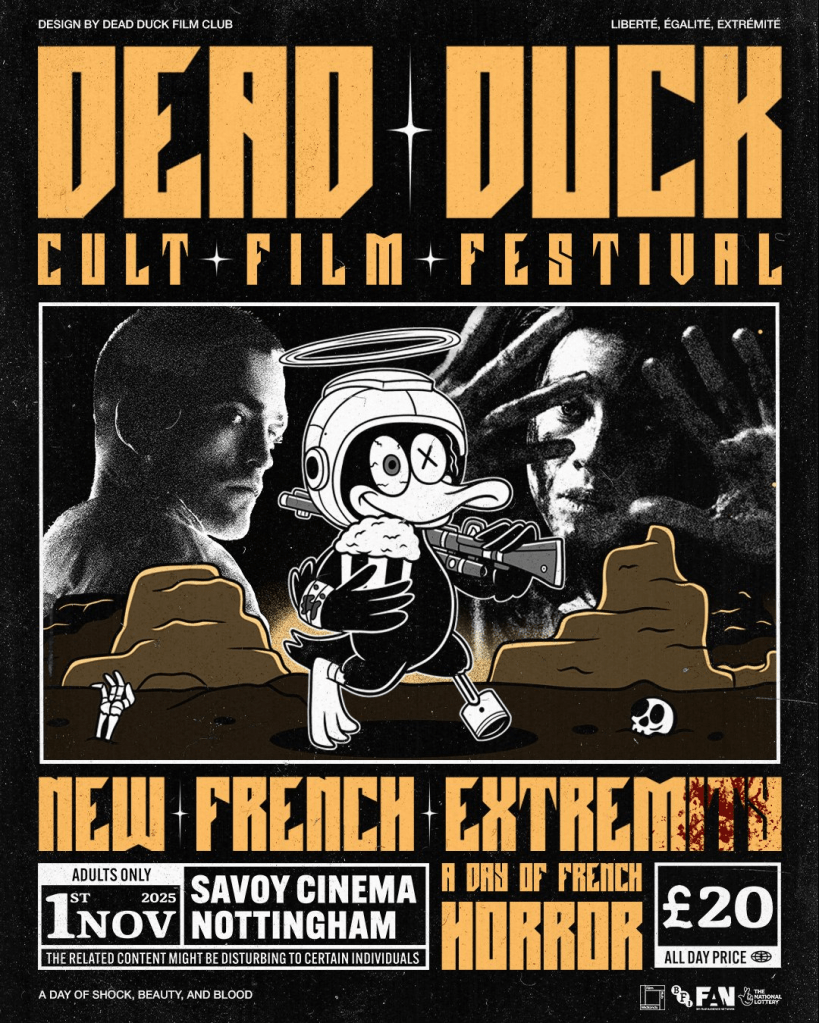

On November 1st, I had the pleasure of attending the Dead Duck Film Festival at Savoy Cinema in Nottingham. The festival was organised and hosted by Nottingham’s own Dead Duck Film Club, an incredible collective of amazing people with a passion for all things film. They have made quite the splash on social media recently, with a series of recorded interviews with local film enthusiasts in Nottingham, as well as a creative marketing campaign leading up to the festival itself, all of which created a consistent and captivating online presence and brand image for the collective.

The festival was themed around ‘New French Extremity’, a sub-genre of film popularised by a wide range of French filmmakers during the early 2000s, noted for their boundary-pushing content often deconstructing a plethora of controversial or underrepresented topics in mainstream cinema, conveyed via means that were, and still are, considered ‘extreme’ by many local and international audiences and critics. Due to the frequently violent, disturbing, and shocking nature of the films situated within this movement, many landmarks of the sub-genre have been prone to criticism but openly welcomed as cult classics by a large quantity of movie lovers. The movement’s fanatics often laud the films as intricately woven confrontations of taboo subjects and analyses of some of the darker, more uncomfortable parts of the human psyche.

The films selected for the festival were (in order) Julia Ducournau’s Titane (2021), Claire Denis’s High Life (2018), Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge (2017), and Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs (2008) – with no two films looking or feeling the same, nor sharing the same message. Across the four films screened, the multi-faceted transgression so synonymous with the movement reared its head, demonstrating a wide array of topics, all approached with a distinct directorial sheen. Sadly, I was unable to attend the final screening of Martyrs, but will delve into the other three movies and my experience of the entire day.

First Impressions: Before speaking on the films themselves, I feel it necessary to not only set the scene but give credit to the immense effort poured into every corner of the festival. The thing that struck me weeks before even reaching the cinema was the sheer passion on display in Dead Duck’s marketing for the festival. As I hinted at already, the team at Dead Duck really went all out on their social media. A steady stream of beautifully designed and laid-out infographics, dynamic and professional-looking posters, short and long-form interview clips, and snappy videos made the festival feel monumental, and the care behind it shone through before the event took place. Upon reaching the Savoy Cinema in Nottingham, my mind was only further blown away by the presentation. Beyond the festival’s logo being projected onto the cinema’s curtains, there were fabulous zines provided to all guests, as well as stalls situated outside the screen where artwork could be bought from local artists. It was an immensely welcoming sight, and foreshadowed the amazing day ahead of me.

TITANE (2021) Dir. Julia Ducournau ★★★★½

The first screening, for Julia Ducournau’s Titane (2021), was my most anticipated of the entire festival. Titane has become one of my favourite films of all time. I truly believe it to be a masterpiece in every sense of the word, and it was the perfect way to start the day. Hot off her renowned feature debut, Raw (2016), Titane won the Palme D’or at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival. Even with the insurmountable praise being lobbied towards the film before it begun its general theatrical release, I do not think I could have anticipated the emotional tour-de-force that was in store for me. The majority of the film’s marketing and media attention was directed towards the grotesque body horror that was already expected of Ducournau. Although, much to my surprise upon a first viewing, much of the film’s ‘horror’ is situated in the first 40-or-so minutes.

The first chunk of the film is fast, ferocious, and deeply angry. However, in one of the greatest tonal shifts in recent memory, the remainder of the film is comparatively quiet and unspeakably tender. The shocking brutality of the first act is re-contextualised as a cry for help and a desperate search for identity and belonging (at least, that is my interpretation). For this first portion of the film, the focus rests on a young woman, Alexia’s, killing spree but, in an attempt to evade capture for her crimes, she assumes the identity of a long-missing child, and is taken in by the grieving single father. This is where the film really begins to blossom and show its true colours. I want to note that I will be using they/them pronouns for the remainder of the review when referring to the lead character, as their exact gender identity is kept intentionally vague once they undertake the transformation. Now under the guise of the 17-year-old Adrien, their edges soften, their violent tendencies become a shell of what they once were, and the relationship between father and ‘son’ becomes actualised. It can be inferred that Vincent, the grieving father, recognises quite early on that this is not truly his son, but he accepts them nonetheless. Even in the hyper-masculine environment that is the fire station at work, Vincent defies masculine stereotypes and wholly accepts Adrien for who they are, even amidst objections from his conventionally ‘macho’ colleagues. As I am sure is clear from the plot outline, the film heavily tackles themes of gender and identity, which is made even more striking when placed in contrast to the barbarity of the first 40 minutes. The body horror that was used to market the film is quickly transformed into a solemn and sensitive tale of body dysmorphia and eventual body acceptance. Through the renewed father-son dynamic, the two central characters are able to fully embrace themselves, all whilst providing what the other needs: Vincent – a son, and Adrien – unconditional love and acceptance from another.

As for my long-awaited big screen viewing of the film… it was everything I had hoped for. The gore at the top of the film felt crunchier and nastier in the cinema, and the moments of vulnerability in the back end shone through more than ever, reducing me to tears on more than one occasion. This was a perfect choice to start the festival, and I remain endlessly thankful to the Dead Duck team for putting this film to the silver screen once again.Within the context of New French Extremity, Titane embodies all that the movement strives to achieve. Cheap, superficial shocks are the least of the filmmakers’ intentions. The contortions of the body and soul in these films can tell us so much about who we are and why we feel so deeply uncomfortable when seeing perversions enacted on the human body. Julia Ducournau understands this mantra and uses Titane to flip it on its head – treating transformation as a thing of beauty and self-actualisation, rather than a source of disgust.

Q&A WITH TITANE EDITOR, JEAN-CHRISTOPHE BOUZY

If my experience watching Titane on the big screen wasn’t perfect enough already, the film was bookended by a pre-recorded Q&A with Titane’s editor, and long-time Julia Ducournau collaborator, Jean-Christophe Bouzy, conducted by Seb from Dead Duck. Bouzy spoke fluently about his time working on the film, his love for cinema, and his long-standing friendship and professional relationship with Ducournau. My favourite portion of the interview highlighted what was also my favourite scene in the film: the moment in the second act where Adrien and Vincent share a dance in the fire house in a perplexingly beautiful display of mutual love and acceptance and the music choice for the sequence, Future Island’s Light House. Considering how perfect the needle drop is, being one of my very favourites of the decade, it was immensely gratifying to hear that it was always baked into the script. Titane is a superbly cut-together film, and hearing a mix of insightful stories and comical anecdotes about the editing process was a privilege to learn directly from the film’s editor.

HIGH LIFE (2018) Dir. Claire Denis ★★★½

Claire Denis’s High Life (2018) was the only other film of the festival that I had seen before, although only once. My memory of it was faint, but very positive. What was surprising, however, was how drastically different the film was on this viewing as opposed to my recollection of it. The most striking thing about High Life is its slow pace. Of the films I saw at the festival, this was the one that, upon talking to people after the screening, the largest number of audience members struggled with. The majority of the responses I heard noted the pacing as conceptually fascinating but ultimately detrimental to the overall experience, leaving many to feel slightly bored. I appeared to be in the minority during this screening, as I found the pace utterly entrancing.

I do not mean to sound hyperbolic, nor to undermine Claire Denis’s distinct director’s touch, but High Life is one of the closest recent films to achieving the same calibre of cinematic hypnotism as Stanley Kubrick’s much celebrated 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). However, High Life never feels like a repeat of that beloved classic, as its structure and contrast between moments of silence with some quietly devastating sequences (which is where the ‘extremity’ part of ‘New French Extremity’ comes into play) is what allows the film to carve its own identity.

I found it tough to pinpoint what exactly High Life was trying to say at points. There is an obvious overtone of corporate critique, which often felt too on the nose for my liking, especially because of Juliette Binoche’s (usually a fantastic actor, one of my favourites in fact) wonky performance as the authoritative figure aboard the space vessel that the film almost entirely takes place on. Although, I believe that there was more under the surface of the film that I could not fully uncover on this viewing that added more weight to the overall product. For example, any moments of sexual violence feel realistically horrifying, without revelling in the misery nor overplaying it for dramatic effect. I just struggled to place the broader meaning of these moments amidst the larger story. As I have already stated, there was much of the film which I did not remember from my first viewing, but a couple of days after the festival, it became clear why. Of the three films I saw at the Dead Duck Cult Film Festival, High Life felt like a daze… as though trying to grasp any sort of tangible memory of it was an almost abstract undertaking. The film moves in such a uniquely transitory way that it defies storytelling convention. I came out of the screening feeling that the film played better as a sensory experience as opposed to a ‘movie’ with character and story arcs. This is a bit of a double-edged sword, as it left me somewhat cold to the film, lacking the lasting impact of Claire Denis’s earlier masterpiece, Beau Travail (1999) – which excels in the similarly melodic pacing, but reaches a point of emotional summit which recontextualises the rest of the film. High Life, conversely, lacks this sense of release as it approaches its climax, with the final act of the film being the segment where the story becomes somewhat monotonous. It leaves High Life feeling as though it lacks resolution, which I am of two minds about. On the one hand, I would have liked the film to have ended on a more striking note. On the other hand, I respect that films generally don’t need to wrap up in a neat little bow, but I can’t help but think that Claire Denis could’ve found a way to have bookended the film in a more impactful manner.

High Life is certainly not for everyone, but it is a true slice of slow cinema, so pure in form in a way that is seldom seen in today’s cinematic landscape. Its hypnotic pace and lurking existential dread are unmistakably bold and, even if that sometimes comes at the cost of a more riveting film experience, I couldn’t help but be swept away by the novelty of such an original approach to the sci-fi genre.

DUCK TALK Live Panel Talk with Dr. Megan Kenny, Clelia McElroy, and Dr. Alice Haylett Bryan

In the middle of the festival itinerary was the ‘Duck Talk’, a live panel where Seb from Dead Duck had a roughly hour-long talk with Dr. Megan Kenny and Clelia McElroy, creators of the Monstrous Flesh podcast, and Dr. Alice Haylett Bryan, an expert on New French Extremity. The panel was truly fascinating and thankfully went slightly overtime, providing even more thought-provoking points of discourse. All three guests brought passion, depth and nuance to the discussion of the movement. Among the most captivating elements of the talk was how each panel member differently defined the boundaries of the movement and genre. As somebody who finds that labelling or canonising films can occasionally be arbitrary and devalue the individuality of a movie’s artistic merit, I really appreciated that all the guests seemed to reflect this sentiment. Each of the guest speakers clearly applied different meaning to the term ‘New French Extremity’, and they each acknowledged the flexibility of how each film screened at the festival fit (or perhaps didn’t necessarily fit) into the canon of New French Extremity. This was an enthralling panel, and it was a real treat to have in the middle of the festival.

REVENGE (2017) Dir. Coralie Fargeat ★½

Revenge (2017) was the third film I was able to see at the festival and it was the only one I had never seen. I faintly remember hearing buzz about the film when it was initially released, but it quickly faded, until Fargeat came back with last year’s mega hit, The Substance (2024). I, much like the rest of the globe, was a massive fan of The Substance. The Substance pulled no punches in the entertainment department, as Fargeat delivered a tightly written, beautifully simple slice of horror entertainment, complete with beautiful set design and an infectious energy. I was excited to backtrack to Fargeat’s feature debut, having heard that, much like The Substance, Revenge maximalised the amount of fun that could be had with its central conceit. Sadly, I did not find this to be the case. There are glimmers of greatness here, and it was somewhat satisfying to have already seen her follow-up film and see how great of an improvement it was. But, as it stands, I found Revenge mind-blowingly dull for such a simple and seemingly safe premise. Revenge did not manage to justify its existence for me. Beat-by-beat, I could not shake the feeling that I had seen every idea in the film done before and executed to much greater effect.

To briefly touch on the ‘Duck Talk’ yet again, a couple of the panel members remarked that they found the attempts to subvert and reclaim the male gaze somewhat shallow in Fargeat’s films. While I found that the overt gratuity of The Substance’s lingering shots of the female body struck the perfect balance of satirising the male gaze without necessarily replicating it, I felt that, when used in the early portions of Revenge, the same impact was not captured. The use of the male gaze feels ultimately hollow, because the rest of the film ceases to commit to any sort of satire. The men in the narrative commit conventionally ruthless acts of violence very early on, leaving little room for satire when they are portrayed as such simple, cut-and-dry ‘bad guy’ stereotypes, leaving the film in a limbo state between satire and something much more run-of-the-mill, without exactly committing to one or the other. Unfortunately, this meant that the film came off as nothing more than the most standard rendition of a ‘revenge’ film possible (the simplicity of the film’s title sadly echoing the blandness of the concept’s execution). Considering that the film doesn’t even reach the two-hour mark, I was shocked by quite how bored I was. I am somebody whose attention rarely wanes during a film, but I found myself completely fatigued by the time that the film reached its climax. Instead of anticipating the narrative’s every move, it felt more like a slog getting through its overly predictable plot beats so that I could hopefully be genuinely shocked or surprised by something further down the line – a dopamine rush that never came to fruition.

As a part of the New French Extremity canon, it sadly failed on all fronts in my opinion. The real-world parallels are too thinly veiled to have any true impact, and the ‘extremity’ that is scarcely littered through the film comes in moments that are too few and far between to really elicit any notable reaction from me. Revenge never feels challenging nor surprising. Even on the most superficial level (probably the level where The Substance operates the most effectively), Revenge struggles to stand out in a sea of remarkably similar action-revenge thrillers. Revenge feels like wasted potential. There was a huge sandbox to play in here, and I believe that it didn’t make good on that promise.

CONCLUSION

Although I was unable to attend the final screening of Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs (2008), my experience at the Dead Duck Cult Film Festival nonetheless felt complete and wholly satisfying. With the perfect amount of supplementary material, from the countless essays found in the provided zines to the remarkable Duck Talk (something I hope will return to future Dead Duck screenings), this was more than simply an assembly line of films shown consecutively. This was a labour of love. From the moment the festival was announced, to even two weeks after it finished, I remain endlessly in awe of the effort put into the entire day. There was no shortage of things to love, with a fabulous lineup of films with something for everyone, splendidly demonstrating the multi-faceted nature of the New French Extremity movement. Thank you so much to the people at Dead Duck for inviting me. This was a truly wonderful event, and I will be keeping a keen eye on whatever comes next.

Samuel Leary (@themovieguysam on Instagram) is a Nottingham-based film enthusiast and lead programmer for film collective, Club Jok. He is dedicated to sharing his passion for all things cinema and aspires to highlight the power of film through both his writing and curation.

Leave a comment